Edward Bawden (1903-1989) was a witty observer of contemporary life and his designs are a good record of mid-20th century England. He was arguably one of the greatest British graphic artists of the period. His work appeals to me partly because I was trained to do graphic work like his: at school, our Slade-trained teacher showed us how to design posters and book jackets designs using bold outline, flat colour, simple shapes, counterchange and hand-drawn lettering, and she showed us us Bawden’s work to inspire us. Every graphic designer had to be able to do hand-drawn lettering then and we spent hours learning the dimensions of the Gill Sans font.

Bawden was a CBE, a Royal Academician, a trustee of the Tate Gallery and received many other honours. He achieved success and recognition through the quality of his work and presumably because of his dedication, but he was shy and didn’t push himself. It’s hard to imagine an artist without push achieving such success today. He was prolific and there are scores of books, magazines, posters and ephemera to be found with his designs. His work remains popular and he’s held in great affection. He bequeathed his work to the Cecil Higgins Gallery in Bedford, who occasionally put on exhibitions. He was a war artist and did serious graphic work in France and the Middle East.

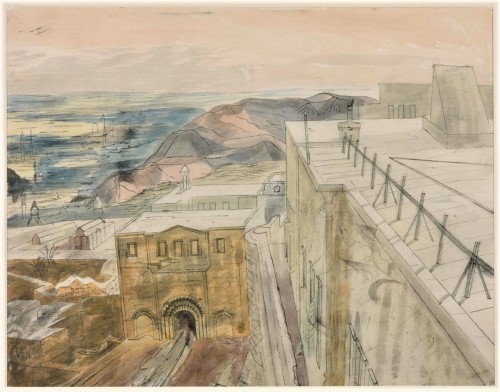

Cairo, the Citadel: On the Roof of the Officers’ Mess, c.1941. Tate Gallery

In her obituary in The Independent, Frances Spalding said, “He recognised no distinction between the artist and the designer. His interest in craftsmanship placed him in a tradition that looks back to the Arts and Crafts Movement.” Digital design has made nearly all of Bawden’s methods antique. There are still good illustrators around but it’s now possible to get by as a graphic designer without being able to draw at all: a designer recently admitted to me that she couldn’t make original images and relied on what she could download from online libraries.

Bawden had a small circle of friends and didn’t relish public engagements. Spalding relates that, late in life, when he was deaf, he was persuaded to go to a dinner held by Tarmac, whom he’d done some designs for. One of the directors talked to him at length about Tarmac’s charitable work while Bawden doggedly ate his dinner. His interlocutor spoke louder and louder and finally asked him what charities he thought Tarmac should be supporting. “Road accidents?” he suggested.

Peyton Skipwith, who promoted his work, recalls that Bawden had a curious love of money coupled with a strong disdain for it. When Skipwith put some of Bawden’s drawings on sale, Bawden pretended to be horrified at the price asked, but became content when Skipwith suggested he cross the road and look at the price of shoes. “With typical perversity, from then on he insisted that I always checked the price of shoes before pricing his own work.”

Bawden was educated at the Cambridge School of Art and the Royal College of Art (RCA), where went on a scholarship in lettering and calligraphy. One of his teachers at the RCA was Paul Nash, from whom he learned the use of the starved brush dipped in dry paint and dragged across the paper to leave streaks of white showing under the colour. The technique was used to even better effect by Bawden’s friend and contemporary at the RCA, Eric Ravilious.

Bawden’s strength was his ability to design for print. He made many lithographs and linocuts, typically printed in four or five flat colours, which transferred well to the commercial press. While still a student, he was taken up by Harold Curwen of the Curwen Press and asked to design a booklet for Carter Stabler and Adams of the Poole Pottery. Bawden spent a year working at Curwen and acquired a thorough knowledge of reproduction methods. Harold Curwen changed his stolid family firm into one of the artistically most important and technically most advanced presses of the 20th century. Bawden’s work was part of its artistic transformation.

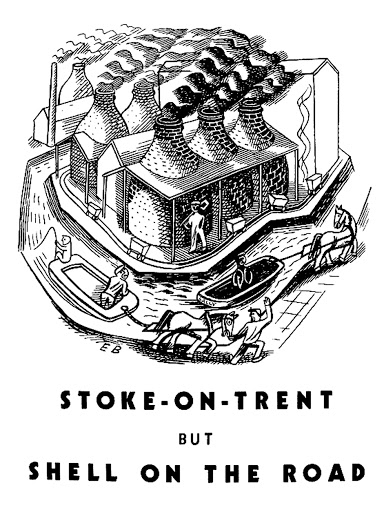

Bawden became better known in 1928 when he was asked to do the drawings for a series of press adverts for Shell-Mex and BP (above). These had amusing captions and amusing drawings – Bawden said that in the 1920s, “amusing” was a widespread term of approval. Press illustration until that time had tended to be either literal or comic and Bawden’s approach to the Shell ads drawing was considered “modern”. He then went on to work for Midland Bank, Twinings, Fortnum and Mason, London Transport, the Folio Society and the Saffron Walden Labour Party. His pictures for Midland Bank were amusing. The little picture below for Midland Bank recalls Alfred Wallis, the naïve Cornish painter.

His illustrations for the Folio Gulliver’s Travels (below) (1965) were lithographs printed in flat red, blue, grey, black and yellow inks, not in half-tone. By changing the dominant colour in each picture and the way in which one colour is printed over another, which yields another colour, Bawden achieved greater richness and variety than you would think possible with five inks. This method is now more expensive than full colour printing.

All the Gulliver pictures are reproduced here.

Mr Fortnum meets Mr Mason. (1939)

His design for Fortnum and Mason uses black, grey and red. The line drawing has the quality of woodcut and the tones are varied by Bawden’s use of solid washes, sponging and shading with parallel lines.

His monochrome drawing of the penguin pool at London Zoo done in the 1930s is treated sparely, with little black, and captures the brilliant white of Lubetkin’s design.

Bawden’s work may not have developed much but he had a wide repertoire of styles and methods. He illustrated cookery books by Ambrose Heath, now so old-fashioned that the books are only worth collecting for Bawden’s decorations. The title page of Good Soups demonstrates his skill at varying line weight and depth of black, his ability to suggest colour through the counterchange in the roundels in the margin (black-on-white on the left, white-on-black on the right) and his educated hand lettering. The bird stealing the pea is typical.